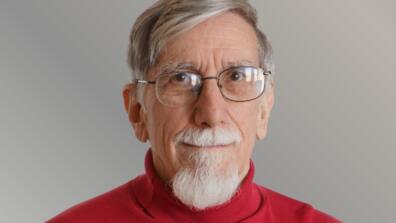

Authors: Thomas J. Christensen and Keren Yarhi-Milo

Affiliation: School of International and Public Affairs- Columbia University; Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs

Organization/Publisher: Foreign Affairs

Date/Place: January 7, 2022/ USA

Type of Literature: Article

Word Count: 1784

Link: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2022-01-07/human-factor

Keywords: Robert Jervis, the Role of Human Factor in Decision Making, Psychology of International Politics, and International Relations Theories

Brief:

Early last December, the field of international relations lost one of its most prominent theorists, Robert Jervis, the founder of what became known as “the Psychology of International Politics.” The article presents an overview of Jervis’ scientific and professional legacy over more than six decades. His theoretical contributions, especially those relating to the role of the human factor, the perceptions and formative experiences of decision-makers, remain of great importance in our understanding of current international politics. His brilliant ideas reflected a complete embrace of the complexity of international politics. The article’s first part highlights the early attention that Jervis showed in his writings regarding the crucial role of human psychological factors and the perceptions of decision-makers in our understanding of policymaking and the complexities of international politics. Jervis laid the foundations for “the Psychology of International Politics” in his two books: “The Logic of Images in International Relations” and “Perception and Misperception in International Politics”. The two books demonstrated the close relationship between the behavior of leaders towards international issues on the one hand, and their cognitive biases, previous beliefs, and personal experiences on the other hand, more than the link between these behaviors and objective circumstances. His interest in the way policymakers think made him interested in reputation and credibility issues, as he believes that leaders should pay attention to how foreigners view them and their countries, as observers of their actions determine the issue of credibility more than the concerned leader or country. Reputation is inherently a subjective matter of perceptions subject to cognitive biases and private motives. Jervis recognized that leaders’ anxiety about protecting and enhancing their own reputation often motivates them to take bold action that might otherwise be difficult to explain. Moreover, observers’ differing perceptions of the meaning of a particular state’s behavior make them believe different things about the state’s capabilities, willingness to bear the pain, intentions, and national interests. Thus, while planning future interactions, allies may draw divergent conclusions about adversaries. One of the examples in which Jervis proved the importance of the psychological approach in understanding international politics was his analysis of the “Domino Theory” during the Cold War. The theory had a motivating effect on American leaders to intervene in parts of the world during that era. They believed that if one state fell to communism without a fight, others would soon follow. The theory had such a psychological effect on anti-communist leaders that they believed in it and acted according to it even without the theory being tested in practice.

The second part continues to present some of Jervis’ intelligent theoretical observations relevant to the psychology of international politics, particularly regarding the behavior of policymakers during crises. Jervis attached importance to the issue of credibility while studying crisis management, coercive diplomacy, and nuclear deterrence. He realizes, for example, that deterrence is a bargain: it requires a real threat of punishment if a target behaves in proscribed ways and a credible assurance that the target will not be punished if it complies with the demands of deterrence. Jervis emphasizes that assurances are an essential part of deterrence, and to know their effectiveness, one must study the target’s perceptions, not those of the deterrent party. Yet, Jervis notes, policymakers often fail to understand this lesson. Take, for example, Obama’s statement that Bashar al-Assad “must go” as part of any effort to resolve the Syrian civil war. “Once Assad’s demise became an essential negotiating demand of U.S. coercive diplomacy (without assurances made that his personal interests would be protected), he had no incentive to adjust his behavior in ways desired by the United States.” Thus, Jervis explains, “the failure to offer credible assurances undercuts deterrence just as much as the failure to level credible threats does.” The article also cites Jervis’ psychological analysis of the “Security Dilemma” as one of his most original contributions. His 1978 “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma” is one of the most influential articles in the theory of international relations. The authors also talk about the addition made by Jervis’ book “The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution” in the field of Strategic Studies.

The final part provides an idea of Jervis’ instrumental contribution to Intelligence Studies and his devotion of some of his work to improving the performance of the US intelligence community, and helping it understand why there have been intelligence failures in its history and how to overcome similar ones in the future. For example, after the invasion of Iraq, many analyses assumed that the reason for not finding stores of weapons of mass destruction was because the Bush administration deliberately distorted intelligence in order to justify the war, but Jervis came to a different conclusion, which was unpopular among his academic colleagues. He argued that flawed intelligence tradecraft by career professionals, rather than partisan politics, accounted for the disastrously wrong intelligence estimates. Besides his genius and prolific production, Jervis was a brave scholar who challenged prevailing views. In addition, the article mentions some of Jervis’ virtues like his scientific integrity, as he warns his students of his cognitive biases that may affect his analysis and work. With his passing, the field of IR has lost a truly great academic mind.

By: Djallel Khechib, CIGA Senior Research Associate