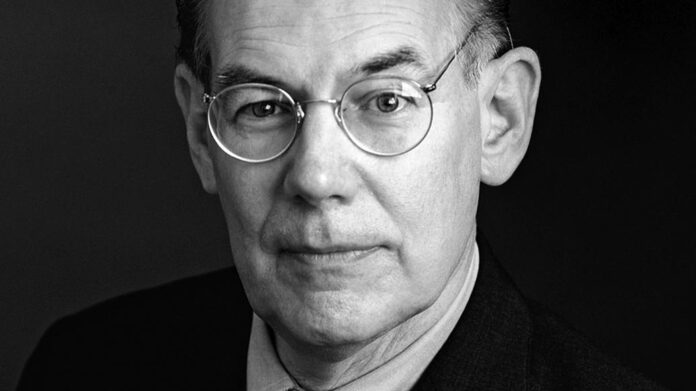

Author: Adam Tooze

Affiliation: Department of History at Columbia University

Organization/Publisher: The New Statesman

Date/Place: March 8, 2022/ UK

Type of Literature: Article

Word Count: 2213

Link: https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2022/03/john-mearsheimer-and-the-dark-origins-of-realism

Keywords: John Mearsheimer, the Origins of Realism, German Geopolitics, Imperialism, the Ukraine War

Brief:

In the wake of the ongoing Ukrainian war and the unmasking of the geopolitical struggle between Russia and the West, the Realist Paradigm in International Politics is experiencing a remarkable recovery, especially with the perspectives adopted by its contemporary pioneers led by John Mearsheimer. Contrary to the narrative being pushed by the mainstream in the West, in which Putin bears full responsibility, the United States and its allies bear most of the responsibility for what is happening in the Ukraine. In this article, British historian Adam Tooze provides a critical reading of “Mearsheimer Realism”, arguing that it has “dark imperialist” origins dating back to the era of expansionist German geopoliticians and geographers in the late 19th century. He also argues that realism fails to grasp the real drives for states resorting to extremist and violent means like war, such as its failure to realize Putin’s motives for invading Ukraine.

At the outset, the author explains the context in which his article came. In the midst of the ongoing Ukrainian war, a YouTube video of a lecture given by John Mearsheimer in 2015 has gained widespread popularity. In the video, Mearsheimer blames the West for what was happening in Ukraine, at the time warning of the bleak consequences that await Ukraine and the West because of Washington and its NATO allies’ insistence to expand eastward toward Russia, ignoring Moscow’s concerns and interests (the lecture is based on an article he wrote in Foreign Affairs in 2014). Since being posted on YouTube, the video has reached 18 million views. Despite the current massive Western mobilization against Russia, Mearsheimer is still delivering the same message. This has once again caused wide anger against him following an interview he conducted with the New Yorker in early March, which came after the Russian Foreign Ministry cited his argument in a tweet. The video, the tweet, and the interview sparked a wave of condemnation against him in the United States that reached Chicago University, where he teaches, and he was even accused of being paid by Russia.

The author agrees with Mearsheimer’s argument regarding NATO’s role in growing Russia’s fears, and also criticizes Washington’s hubris and its promises in 2008 for Ukraine and Georgia to join NATO, describing it as a disastrous mistake. However, this does not make Mearsheimer’s explanation of the Russian invasion correct. The result reached by the theory is nothing but a foregone conclusion of the assumptions from which it proceeds when we think about what is happening in Ukraine. His theory assumes that Russia is a great power. Great powers seek to protect their security and “spheres of interest” just as the United States does (the Monroe Doctrine and the Carter Doctrine, which extends American interests to the Persian Gulf). These interests/spheres are defended by force if necessary. Anyone who does not recognize this fact will fail to grasp the violent logic of international relations. The author describes Mearsheimer’s perspective as lacking an understanding of Russian or Ukrainian history, and its impact will be bleak for Ukraine. It will forever be curtailed by the fate of being within Russia’s sphere of influence. Mearsheimer does not deny Russian aggression, he simply takes it as a given.

In the subsequent part, the author discusses what he claims to be the origins of Mearsheimer’s realist theory. He denies its intellectual genealogy to the writings of the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, as the realists explain, or even from the realpolitik of the age of Bismarck. Rather, he considers it as an extension of the imperialism that has grown with German geopolitics, especially since Friedrich Ratzel in the late 19th century, which prevailed during the interwar, and its pioneers were associated with Nazism. In his view, realism is an “invented tradition” assembled ex-post by the discipline of IR as it established itself at American universities in the Cold War era. For his argument, Adam Tooze cites a recent book by German historian Matthew Specter entitled “The Atlantic Realists: Empire and International Political Thought Between Germany and the United States.” Specter argues that there is a plausible line of descent that derives from a group of the expansive naval theorists and geographers of the pre-1914 period, such as Ratzel and Mahan, through to the interwar German geopoliticians, especially Karl Haushofer and Carl Schmitt, and from there to the classic texts of American realism, notably the writing of Hans Morgenthau. The logic of Mearsheimer’s thinking does not differ from the logic of them, especially Carl Schmitt whose theory of “Grossraum” divided the planet between large spatial blocs, each dominated by a major power. The idea is similar to the realist vision which divides the world into “spheres of power” or “spheres of interest” or “spheres of influence”. Many German geopoliticians found themselves in the dock of Nazisim after the end of World War II. To overcome this embarrassment, as Specter argues, realism in the United States “had to invent a new history for itself which positioned it as a more abstract theory, detached from its imperialist’s roots.”

The author then attempts to prove that realism fails to realize the motives of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and considers that it is incapable of realizing the qualitative shift implied by the opening of hostilities, and why Russia (or any other power) resorts to extreme and dangerous means. Moreover, he argues that officials in the Russian Foreign Ministry itself were skeptical that Putin would take the option of war because they did not see a good reason for Russia to risk using all-out means of war against Ukraine with all its hazards, uncertainties, and costs. The war has a bad record in terms of its desired results, as it is hard to name a single war of aggression since 1914 that has yielded clearly positive results for the first mover. A realism that fails to recognize this fact and the consequences that most policymakers have drawn from history does not deserve the name. In sum, the Ukrainian war pushes us to conduct a real revision of realism. Adopting a realistic approach towards the world “does not consist in always reaching for a well-worn toolkit of timeless verities”, especially for understanding a complex and ever-evolving world.

By: Djallel Khechib, CIGA Senior Research Associate