Author: Andy Hanlun Li

Affiliation: London School of Economics and Political Science

Organization/Publisher: ECPR Standing Group on International Relations (SGIR) and the European International Studies Association (EISA)/ European Journal of International Relations (SAGE)

Date/Place: Volume 28, Issue 2, June 2022 / Erfurt, Germany

Type of Literature: Journal Article

Number of Pages: 26

Link: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/13540661221086486

Keywords: China, International Relations, Eurocentrism, International History, Territorial State

Brief:

The author conceptualizes the emergence of China as a territory, by using a non-Eurocentric knowledge and framework. The author questions whether there are alternative epistemologies of modern territoriality. Using China as a case study, the author shows the polycentric nature of territorialization. He finds that unlike other empires that disintegrated into smaller territorial nation-states, the last empire—called Qing empire—bundled the territorial base for China. He concludes that the modern China has its own deep history of territorialization, which is not defined by the hegemonic nature of Eurocentrism. This article is not necessarily anti-Western, but its aim is to present the Chinese’ knowledge in the history of its own territory, which has been dominated by the European narrative.

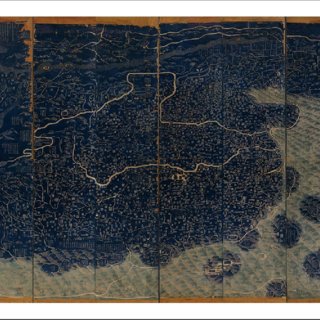

Most of the scholarship on modern territoriality is restricted to Europe and its colonial history. Not much work has been done to trace the alternative epistemic origins of modern territoriality. The author fills that research gap by analyzing the territorialization of China using the Sinocentric perspective. By means of empirical study, the author seeks to problematize the assembling of China as a Sinocentric ethnocultural concept within the territorial limit of the Qing dynasty. This modern and Sinocentric form of territoriality embodies areas that are still considered as foreign and non-Chinese. He moves beyond the usual critiques of modern territoriality and uses the framework of territorial metamorphosis from the Qing empire to the modern China. The Multiethnic Qing empire lasted almost three centuries and assembled the territorial base for modern China. In order to explain the territorialization of the multi-ethnic Qing empire, the author engages empirically with the cartographic and textual representations of China from Confucian literati scholars, European Jesuit cartographers, and the Manchu Imperial Court from the 17th to the early 19th centuries. He finds that by the early 19th century, a new territorialized concept of China had emerged, which closely resembles the modern territory. With China as a case study, the author makes the case for the poly-centric account of modern territoriality, since Europe has turned this concept unidirectional and hegemonic.

The modernist conception of territory is understood as a way to control and regulate space so as to maintain the colonial and hierarchical orders, through the conceptual difference between Europe and its colonies. However, the problem with exclusively focusing on the histories of European colonialism is risking one Eurocentric concept with another. For instance, replacing European nation-state with European colonial state or, Westphalian sovereignty with racial sovereignty. The European derivation and domination over the concept of modern territoriality shows territory as being the byproduct of European historical agencies. Also, at the same time, the rest of the world is reduced to being Europe’s laboratory. If the discussions continue with the European understandings and meanings of territory, then all the other meanings of territory drawn from parallel projects are limited. The theoretical implications for any form of knowledge and practices outside the Western world go unheard, even if they are strong and important critiques of Eurocentrism. Any polycentric origins of modern territoriality are very often negated, and such is the hegemonic nature of Eurocentric forms of knowledge.

The territorialization of China has been perceived as a remarkable historical development in the history of International Relations. Unlike Russia and the United States, China has been able to retain its early modern continental colonial possessions. China did not fragment like Russia into small territorial states. The other multi-ethnic empires such as French and Ottoman empires disintegrated, resulting in the emergence of small states, however, contemporary China continues to preside over a continental empire that originated from violent expansions in the early modern period. The author argues that the case of China is by no means unique in minimizing the territorial distinctions between colonies and empire in itself, however, it is unique in the sense that China was transformed from a geographical and cultural component of the Qing empire to a core successor and dominion of that empire. In the past couple of years, the scholars in Historical International relations have started to examine the plurality of polities and international systems of sovereign territorial states. The author examines the existing International Relations and elucidates the emergence of modern territoriality in China in three stages. In the first stage, the author identifies the Eurocentric diffusionist historiography of modern territoriality in IR postcolonial and constructivist scholarships. In the second stage, he argues that China is not a singular, historically continuous polity occupying a state territory inhabited by different ethnocultural groups. The final section focuses on the emergence of a geographic understanding of China as a landmass and environment, defined by the contours of the Qing Empire, in the early 19th century.

According to the author, the key aspect of the East Asian Confucian International system is the Hua-Yi distinction. It distinguishes people considered civilized based on universal Confucian values from those who are not. This distinction is not only a form of self-other distinction, it has more to do with the otherness based on territoriality. The author asserts that Hua and Yi are not fixed or spatial designations, but they have been manipulated by the elite educated class for meeting their political ends. When the Ming empire collapsed, the Hua-Yi distinction persisted among the Han Literati class in designating the geographical borders of China. This distinction was mostly serving those serving the new empire and for those who were against the new ruling Manchu dynasty. One of the attempts to interpret the Hua-Yi distinction in the 17th century signifies that the difference between China and other had to primarily do with the bloodline, geography and habitat and not any cultural differences.

Based on these distinctions, the later-day Chinese Nationalist leaders were not forced to adopt modern territoriality based on European imperialism. They rather followed the already existing territorialized conception of China in their experiments with nation-building and state-building. The Chinese case shows that modern territoriality has multiple and connected origins, rather than being drawn from one singular notion. This polycentric understanding of modern territoriality questions the simple binary of Eurocentric IR and anti-Eurocentric IR. The reclamation of territorialization of China is an important transformation in the history of International Relations, not as a counter-hegemonic project, but to normalize the non-Western concepts and practices.

By: Saima Rashid, CIGA Research Associate