Author: Stephen Walt

Affiliation: Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government

Organization/Publisher: Foreign Policy

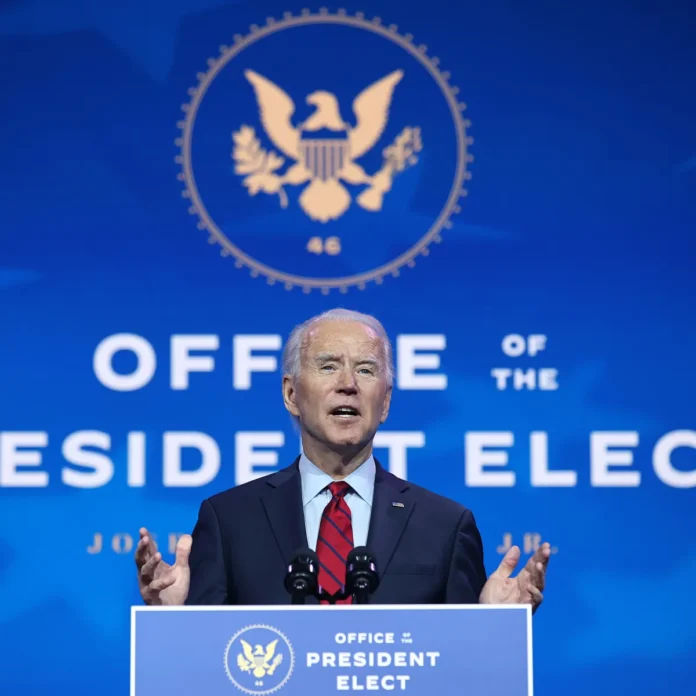

Date/Place: December 11, 2020/USA

Type of Literature: Analysis

Word Count: 2100

Link: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/12/11/biden-sees-the-a-team-i-see-the-blob/

Keywords: Biden’s Coming Administration, the Blob, Liberal Hegemony, Real Concerns, and the Limits of US Global Leadership

Brief:

With Biden and his team’s approaching assumption of duties in the White House, American writers, experts and politicians have different impressions regarding the persons that Biden chose in his administration, and different expectations on the changes that he will bring about at the local and global levels alike. While some consider his team to be a “blessing from heaven,” as it came at a very convenient time after the chaos caused by Trump, others warn about this administration as Biden and nearly everyone he chose publicly supported the 2003 Iraq war, with some writers even explicitly indicating that “The Blob was Back and Ready for War.” In this article, Stephen Walt presents a number of reasons that explain his concern about the coming administration, especially since he sees it as merely an extension of the mainstream inside the United States, i.e., “the liberal hegemony” that was behind previous disasters that undermined the US’ global power. However, he stresses the need to ask about their future plans and what Biden and his liberalist team will do during the next stage, instead of judging them based on their previous mistakes. He argues that it is difficult for anyone to know exactly what they will do and how they will deal with issues, especially with new emergency events that were not on their agenda before assuming power, citing what happened with G. W. Bush and 9/11 events, Obama and the Arab Spring, and Trump and the COVID-19 pandemic. Each of them encountered new circumstances that were not taken into account, which contributed to distorting his agenda and causing many failures. As for the reasons that make the author anxious about the upcoming administration, he points out the following: (1) The liberal internationalism of Biden and his team, which believe in the US’ global leadership, as Biden himself expressed in his article last March in Foreign Affairs, as well as the belief in “American exceptionalism” as expressed by Jake Sullivan (his national security advisor); both of which insist on the US’ ability to lead the world again despite their awareness regarding the end of the unipolar era. They believe in Washington’s ability to remain committed to allies, that it should bear the burdens, and needs to undertake the solution of the world’s problems. The author asserts here that the US’ insistence on excessive commitment and leadership in every issue would provoke immediate resistance from powers such as China and Russia. This will tempt its allies, by pushing it to assume an unequal share of burden, just as engagement in solving every problem across the world is not necessarily in the US’ interest. (2) Biden refers to ideas whose application requires interference again in other countries, telling other societies what to do and how to live, i.e., to engage in social engineering efforts that have proven their failure before, as well as the impossibility of predicting their results. (3) Biden makes a long list of global commitments that require more time, more resources, and concerted efforts. The new administration will not be able to carry out even half of this list. (4) The similarity in world perspective between members of the incoming administration and their nostalgia for previous eras of American global primacy is indeed disturbing, “when all think alike, no one thinks very much,” as Walter Lippmann once said. It will be difficult to draw attention to other perspectives that offer alternatives and solutions or alerts to risks. (5) Biden’s explicit commitment to liberal democracy will cause him more problems than it leads to solutions. How, for example, will he deal with allied countries whose democracies do not live up to liberal ideals such as India, Hungary, and Israel? Making democracy the pillar of his foreign policy would transform the US’ rivalry with China into an ideological competition that would impede cooperation on issues such as climate change, and make the long-term possibility of coexistence less defensible. This will lead to falling back into the “regime change” trap that has produced catastrophic swamps in regions such as Afghanistan and the Middle East. (6) Biden will receive a long series of “beggars” requests. The European allies will want to know what he will do on issues such as the Ukraine, and the Turkish-Greek rivalry. The Asian allies will request more help to counterbalance China, and Washington’s traditional clients in the Middle East will also push hard to prevent Biden from joining the nuclear deal with Iran; if he goes forward, they will push for more American weapons and additional security guarantees as compensation. Additionally, the problems of Afghans, Somalis, and others remain. How will Biden respond when these requests start piling up? Which areas will get priority? and which countries will be told to do more for themselves? Thus, the author confirms his concerns about the upcoming administration whose dictionaries do not know concepts such as “the buck-passing,” i.e., pushing others to take responsibility and bear their heavy burdens, instead of Washington assuming them alone. All of these concerns will complicate the new administration’s mission and burden it on its first day in the White House.

By: Djallel Khechib, CIGA Senior Research Associate