Author: Jonathan Mercer

Affiliation: Professor of Political Science at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Organization/Publisher: International Security

Date/Place: October 1, 2023/ UK

Type of Literature: Journal Article

Word Count: 12412

Link: https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/48/2/7/118111/Racism-Stereotypes-and-War

Keywords: Russo-Japanese War, Conflict, Interpretation, Policymakers, Racism

Brief:

Racism distorts policymakers’ analyses of allies and adversaries’ capabilities, potentially leading to costly decisions in war and peace. One example is the Russo-Japanese War, where racist beliefs influenced inaccurate predictions. Despite its potential impact, international security scholars have largely overlooked racism’s role, assuming that decision makers are rational agents. The author however challenges this assumption by demonstrating how racist beliefs systematically influence policymakers’ perceptions.

Focusing on two key characteristics of racism, Mercer examines its impact on policymakers’ explanations and predictions. Using the Russo-Japanese War as a case study, he explores how racist beliefs affected assessments of Japan and each other, while also considering how reputations easily become stereotypes, and the broader implications of intolerance in international politics.

The article is divided into seven parts. The first part emphasizes how the credibility of policymakers is determined by their assessment of each other’s capabilities, interests, and determination regarding a given conflict or issue. Evaluating whether a state can uphold a commitment involves considering its economic size, military strength, interest in the specific issue, and willingness to risk war. Racism consistently shapes how policymakers perceive these aspects of credibility. By identifying characteristic patterns of racism, the author establishes two expectations regarding how policymakers’ racial biases affect their interpretations and forecasts of their allies and adversaries’ actions.

As for the first expectation, racist policymakers tend to attribute behavior to inherent traits rather than external circumstances, shaping their views on military capabilities and governance. Despite the decline of biological racism, racial categorizations persist, influencing perspectives on various groups such as the “inferior yellow races.” This mindset can lead to dismissing the interests of racially categorized groups, as seen in George Kennan’s doubts about the capacity of black South Africans for self-governance and his suggestion that African Americans were unfit for voting. Additionally, the second expectation indicates that racist policymakers rely on stereotypes to predict and explain behavior, offering perceived predictive and explanatory power based on assumptions about certain types of individuals. Confidence in these beliefs significantly influences their impact, with stereotypes enduring due to assimilation, a pervasive cognitive process described by Robert Jervis. Despite their often-inaccurate nature, stereotypes persist, distorting analysis and perpetuating a cycle of ignorance, contributing to the enduring influence of racist stereotypes on credibility assessments.

The second part of the article suggests how security experts have often overlooked racism’s influence on credibility assessments, even in cases involving historical racist policymakers. Policymakers tend to evaluate credibility based on objective assessments of capability, interests, and resolve, often disregarding their own biases. While this argument may seem improbable, it provides a theoretical explanation for downplaying racism’s impact. Another less realistic view suggests racist policymakers have never existed, hindering the study of racism’s influence. Despite this oversight, normative or rationalist decision-making models advocate for assessing behavior without preconceptions, promoting objective interpretation known as “updating.” Unlike assimilation, which uses beliefs to interpret data, updating uses data to inform beliefs. Reputations, unlike stereotypes, rely on updating, allowing policymakers to revise their assessments based on behavior. Over time, divergent reputations converge and become more accurate. Unlike stereotypes, reputations change as policymakers update their beliefs.

Evidence opposing Mercer’s argument would support the rationalist view of credibility, suggesting that both racists and non-racists assess credibility similarly. Rational choice arguments apply best when the stakes are high and the players few, according to Morris Fiorina, thus expecting similar and objective credibility assessments from both racist and non-racist policymakers. To test these theoretical expectations, the author chose the Russo-Japanese War for its historical significance and extensive research, enabling examination across different states and policymakers. While some may critique the selection, arguing that it appears straightforward or of solely historical interest, the conflict’s depth offers insights into the impact of racism on credibility assessments. Despite views that racism is outdated, its persistence underscores the importance of studying how strongly held beliefs, racist or not, can shape policymakers’ perceptions and decisions.

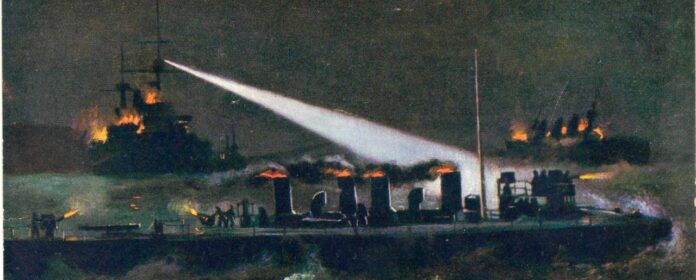

In the third part, the author delves into the Russo-Japanese War and how it shocked the West. Japan, often dismissed as part of an “inferior yellow race,” defeated powerful Russia in nineteen months. Japan’s triumph included seizing Korea, capturing Port Arthur, and defeating Russia’s Baltic Fleet, marking a significant naval victory and one of the largest military engagements to date at the Battle of Mukden.

The conflict, sparked by Japan’s westward expansion conflicting with Russia’s southeastward expansion in Manchuria and Korea, saw Japan cut diplomatic ties with Russia in 1904. Despite warnings from Russian military attachés, Japan’s capabilities were underestimated, leading to surprise at Japan’s victory. The perception of the Japanese as an inferior race had emerged recently, given that earlier European travelers had described them as “white.” By 1900, racial categorization was common, contributing to misconceptions about Japan’s capabilities and leading to global celebrations of its victory over white supremacy.

In the fourth part, Mercer elaborates on the Russian “interpretation” of Japan. Racism led Russia into a war it did not anticipate or win, as policymakers relied on dispositional explanations and stereotypes to assess Japan’s behavior, fostering unwarranted confidence in Russia’s analysis. Initial accurate assessments by Russian attachés in Japan were later overshadowed by racist evaluations embraced by policymakers in St. Petersburg.

The study reveals contrasting perspectives among Russian policymakers regarding Japan’s military capabilities before the Russo-Japanese War. While some, like Lt. Ivan Ivanovich Chagin, Maj. Gen. K. I. Vogak, and Col. Nikolai Ivanovich Ianzhul, provided unbiased evaluations, recognizing Japan’s formidable forces, others, like Col. Gleb Mikhailovich Vannovskii, relied on racist stereotypes, leading to an underestimation of Japan’s strength. Racism among Russian leaders, perpetuated by derogatory attitudes and a belief in white superiority, fueled dismissive attitudes towards Japan’s protests and threats, contributing to a failure to understand Japan’s interests and escalating tensions. Despite initial confidence in a swift victory, Japan’s relentless attacks and naval victories, coupled with delayed responses fueled by racist beliefs, led to humiliating defeats for Russia. However, individuals like Jacob Schiff, rejecting racism, accurately predicted Japan’s victory and played a crucial role in supporting Japan’s success by securing loans, emphasizing the impact of racial biases on credibility assessments and diplomatic efforts.

We see in the fifth part, that in 1900, Germany encouraged a conflict between Japan and Russia, believing it would distract Russia from European affairs and prevent a potential two-front war. The policy aimed to strengthen Germany’s position and undermine the possibility of an Anglo-Russian alliance. However, German attitudes toward Japan and Russia were influenced by racism, with fears of Japan’s “yellow peril” and stereotypes portraying Russians as culturally inferior. Despite evidence of Japan’s military capabilities, German confidence in Russia’s victory persisted, reflecting deeply ingrained racist attitudes among German policymakers and military personnel.

German assessments of the Russo-Japanese War were heavily influenced by racial stereotypes and dispositional explanations rather than situational factors. Despite acknowledging Russia’s logistical challenges, German observers attributed Japan’s victory to racial characteristics and morale, depicting Japanese soldiers as zealous and spirited while criticizing Russian passivity. Stereotypes about Russian officers as lethargic and lacking willpower reinforced dispositional explanations. Even when evidence contradicted German beliefs about Japan, they revised their views to emphasize racial types over situational factors. This racial framing persisted, leading the Germans to predict Russia’s future weakness based on perceived incompetence, eroding Russia’s reputation in Germany. Figures like Friedrich von Holstein and Alfred von Schlieffen expressed confidence in Russia’s inability to pose a threat due to inherent deficiencies, influencing German military strategy, notably the Schlieffen Plan. Despite evidence of Russian reforms, German officials remained entrenched in racial stereotypes, underestimating Russia’s capabilities and resolve, with detrimental consequences in World War I.

In the sixth part, the author demonstrates that British assessments during the Russo-Japanese War were steeped in racial stereotypes and dispositional explanations, reflecting bias against Japan’s capabilities despite its victory over China in 1895. Even after allying with Japan in 1902, British officials remained skeptical and underestimated Japan’s military prowess. Key figures like Neville Chamberlain and Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice expressed confidence in Russia’s superiority, echoing biases that permeated British observations, naval assessments, and predictions of Japan’s defeat by Russia.

Japan’s victory in the war challenged British perceptions of race and power, shifting from derogatory labels to admiration for Japanese bravery. Racial interpretations downgraded Russia’s race and upgraded Japan’s perceived whiteness and civilization, with the British military attributing Japan’s success to Bushido and national resolve. Despite the shift, policymakers still viewed Russia as a threat, overlooking the broader implications of Japan’s victory and signaling a turning point in global race dynamics with the rise of non-white nations on the world stage.

The final part underscores that stereotypes in policymaking can lead to biased interpretations of evidence, reinforcing preconceived beliefs rather than objectively assessing behavior. While both stereotypes and reputations involve generalized character judgments, stereotypes rely on assimilation, where existing beliefs drive interpretations, while reputations depend on updating based on objective assessments of behavior. Policymakers often assimilate information to fit stereotypes, particularly in assessments of race, gender, and religion, which can significantly influence credibility assessments. Encouraging policymakers to recognize stereotypes as distinct from reputations may help them critically evaluate their reliance on generalized beliefs. Racism and bigotry have historically distorted policymakers’ analyses and predictions, leading to unwarranted confidence in their assessments, highlighting the need for objective assessment and critical analysis in international relations.

By: Aseel Khalid, CIGA Research Intern