Author: Valerie Hansen

Affiliation: Stanley Woodward Professor of History at Yale University

Organization/Publisher: Foreign Affairs

Date/Place: September-October 2022/ USA

Type of Literature: Book Review

Word Count: 3165

Link: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/old-world-order-origin-international-relations

Keywords: The Old Chinggisid Order, Westphalian Order, East and West, Eurasianism, Rising Powers

Brief:

In her new book, “Before the West: The Rise and Fall of Eastern World Orders,” Turkish-American scholar Ayşe Zarakol challenges the prevalent Eurocentric perspective among international relations scholars, which takes the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia as the starting point for the modern international order. The mainstream perspective falls into the “trap of Eurocentrism” and affects scholars’ view of how the modern world was formed. Zarakol argues that the rise of non-Western powers in the East necessitates a closer examination of the experiences of early Eastern empires, such as China, India, and Japan, in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the history of international relations beyond the Westphalian order. The book explores the ways in which non-Western parts of the world interacted with each other in the past, forming what is known today as the international order. To this end, the author begins the history of the modern world order in 1206 AD, the year in which Genghis Khan began his rule over the peoples of the Eurasian steppes and established what Zarakol refers to as the “Chinggisid Order.” This order, which lasted for nearly 500 years and extended from China to Hungary across the Eurasian continent, was seen as a model for all subsequent rulers who sought to emulate Genghis Khan’s ambitions to rule the world. The Ming, Mughal, Safavid, and Timurid empires in present-day China, India, Iran, and Uzbekistan, respectively, all sought to claim their place in this order and invoke their historical legacy as they strive for a significant international status today.

The article is divided into three sections. The first part discusses the “Chinggisid Order,” including its features, stages, and diplomatic interactions between its actors and polities. This order, which lasted for nearly 500 years, can be divided into three stages. The first period, which lasted from 1200-1400 AD, was marked by the unified Mongol empire under Genghis Khan and its four successor states in modern-day China, Iran, Russia and Ukraine, and Central Asia. The peaceful coexistence of these regions in the 14th century is considered “the beginning of modern international relation, as rational state interests began to take precedence over religious affiliations.”

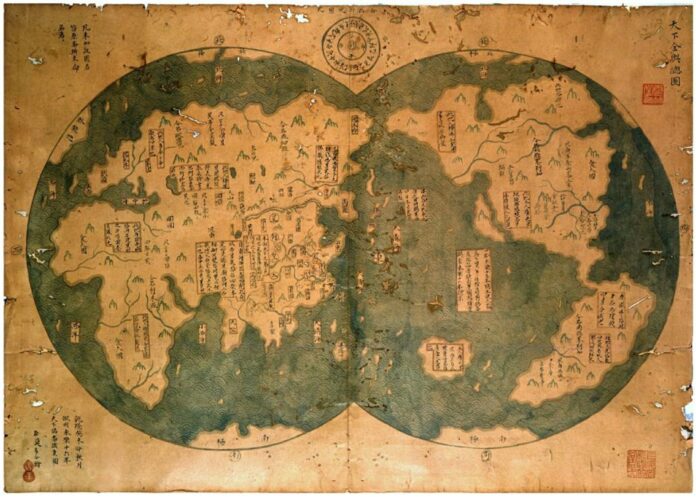

The second period of the Chinggisid Order included the Timurid Empire, led by Tamerlane (1336-1405 AD), and the Ming dynasty in China (1368-1644). The Timurid Empire was established following the model of Genghis Khan’s state, while the Ming dynasty focused on defeating Mongol and Turkish opponents, including the warriors of Timur. In an effort to demonstrate their strength to the world, the Ming emperors even attempted to position themselves as successors to the Mongol land empire and sent their fleet loaded with treasures and thousands of men to East Africa.

The third period of the Chinggisid Order included the “millennial sovereigns,” or “sahibkıran” in Turkish, referring to states that held power, dominance, and victories, of the Mughals, Ottomans, and Safavids. These rulers, although not related to the Mongols, sought, like Genghis Khan, to rule the world and were successful in conquering vast lands that are now known as India, Turkey, and Iran. Zarakol’s book concludes with the weakening of these three dynasties around 1700.

The states of the “Chinggisid order” had several shared features. For example, they did not follow a system of inheritance, such as primogeniture, to choose their rulers. Instead, they employed the “Tanistry system,” which was borrowed from Celtic tribes in the British Isles. This system held that the best-qualified individual should rule the group after the death of a leader, but only if he had proven himself through violent struggles for the benefit of the group and received the unanimous support of the warriors to be their new leader. Throughout the centuries, the rulers of these countries also shared “a particular vision of the whole world” and developed, modified, and reproduced “political, economic, and social institutions” and a diplomatic system similar to the Westphalian one.

In the second part of the article, Valerie Hansen critiques Zarakol’s book, arguing that it is difficult to cover such a long period of time as five centuries and lacks important material on the Chinggisid diplomatic system. Hansen specifically points out that Zarakol ignores two significant references that contradict her claims about the efficiency of Mongolian rule. The first reference is the account of monk William of Rubruck, who visited the court of Khan Mongki, grandson of Genghis Khan, in the Mongol capital of Karakorum in the mid-13th century as a missionary and diplomatic envoy. William’s detailed account shows that the Mongols treated diplomats well but also reveals that the government was not flexible, but rather a strict hierarchy in which only the Great Khan had the authority to make decisions on international diplomatic matters. This contradicts Zarakol’s “rosy-eyed claims” about the efficiency of Mongol rule. The second reference is the experience of Spanish diplomat Ruy González de Clavijo, who visited Tamerlane in Samarkand in 1404. He was sent by Henry II of Castile, to persuade Tamerlane to form an alliance against the Ottomans. However, he was unable to obtain a response from the Great Khan due to his illness and the inability of other leaders to exercise any authority. De Clavijo was eventually forced to escape to avoid being captured during conflicts between aspiring leaders. Hansen argues that these two examples demonstrate the limitations of the effectiveness of the Chinggisid order, as the Great Khan was the only person with the power to make decisions related to foreign relations, undermining Zarakol’s arguments.

The final part of the article highlights the significance of Zarakol’s book in helping us understand how different regions of the Eastern world before 1500 shaped the modern world and what non-Western history can tell us about the present and future. The author argues that a wide range of contemporary intellectuals and politicians in countries such as China, Russia, Turkey, Iran, and Japan believe in the enduring impact of Mongol rule on their societies today. Since the 1920s, Russian scholars have discussed the influence of Mongol rule on modern Russia and even encouraged their leaders to follow in Genghis Khan’s footsteps and unite Russia to build a new empire covering both Europe and Asia, or what is known as Eurasianism. This trend has gained renewed popularity since the fall of communism, and Russian President Putin has even been compared to Genghis Khan. In this context, Russian elites supporting Eurasianism often invoke historical traditions that have no connection to the Westphalia treaty and its outcomes. “The world orders that earlier rulers outside Europe established remain deeply relevant because the people who live in those regions today recall those past exploits and systems and sometimes try to recreate them.”

Finally, Valerie Hansen advises contemporary American leaders to pay more attention to the history of emerging powers in Beijing, Moscow, Ankara, Tehran, New Delhi, and Tokyo, rather than just tracking the movements of their leaders. Hansen argues that understanding the unique history of these political, economic, and cultural centers, which differs from that of Europe and the West, will enable American leaders to effectively navigate the challenges of the multipolar world we are entering.

By: Djallel Khechib, CIGA Senior Research Associate