Author: Somen Banerjee

Affiliation: National Cadet Corps (Indian Navy), Odisha Directorate, Bhubaneshwar, India

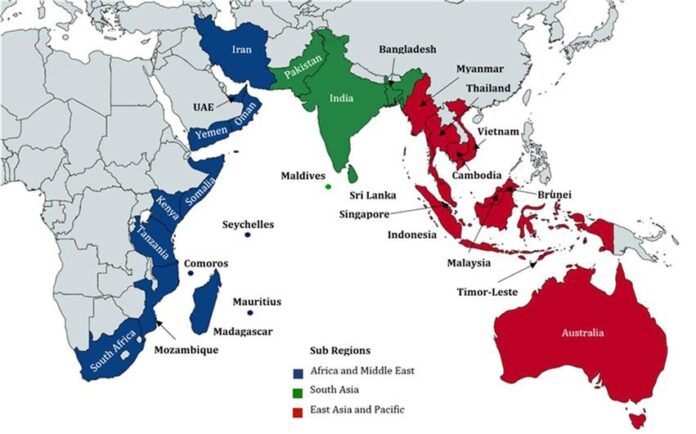

Organization/Publisher: Indian Ocean Research Group Inc; Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) /Journal of the Indian Ocean Region

Date/Place: August 25, 2021/ the UK

Type of Literature: Journal Article

Number of Pages: 13

Link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/19480881.2021.1963913?needAccess=true

Keywords: India, the Horn of Africa, Indian Ocean, Geostrategic Pivot, Human Security, Development

Brief:

By analyzing the compatibilities between India’s goal of Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) and the United Nations’ agenda of Sustainable Peace, the author aims to provide a framework for India’s geopolitical involvement in the Horn of Africa. The Horn of Africa has emerged as a strategic pivot, a region that offers the geographical cause for shaping the universal course of history. The Horn of Africa has become the strategic hub of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) due to the growing presence and interests of extra-regional powers, its unique admixture of conflicts, superpower competition, and contestation between the Middle Eastern States; and, it straddles one of the busiest waterways of maritime trade. India—with the 6th largest Economy in the world—must broaden and deepen its involvement in the region’s geopolitics by harmonizing security and development to contribute to the region and achieve sustainable peace positively.

The author examines the challenges and prospects of working with the geopolitically complex region of the Horn of Africa to achieve a sustainable peace, and strives to address the central questions: What factors make the Horn of Africa an IOR strategic pivot? What distinguishes this area from the rest of Africa? The author examines India’s challenges as a security player in any region, since India has created conflicts from arbitrary border-drawing and shown staggering disregard for social affiliations. Its weak central government has exacerbated and even weaponized these fault lines, causing societal unrest and civil disputes. Accordingly, it must be questioned whether India’s SAGAR framework—which it has used for marine governance to integrate security and development—has the capacity to be implemented in the Horn of Africa, which is rapidly changing. The author analyses the geopolitical significance of the Horn as a pivot of the Indian Ocean Region to determine SAGAR’s feasibility as a foreign policy plan.

The crucial point that the author tries to convey is that orthodox politics no longer determines national stature or power. Instead, the new sources of a country’s international leverage are equally centered on technology, connection, climate change, investment, and trade. The Horn of Africa is not an exception. The region’s security architecture has been shaped by the military presence of several governments and the ever-expanding economic networks in the region. While the U.S., China, the European Union, Japan, and France have emerged as prominent security actors, Russia and the Middle Eastern governments have made considerable inroads in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa is becoming a strategic pivot for the Indian Ocean Region and a microcosm of anarchism in global politics. The security architecture of the area is being increasingly impacted by structural reasons, which has implications for the whole world, as the commercial and military presence of foreign players continues to grow.

The Horn of Africa’s geostrategic relevance has increased significantly over the past ten years due to the fierce military and geoeconomics struggle. Therefore, it will soon become a strategic pivot in the IOR. Although geoeconomics rivalry in the region has brought developmental outcomes and has boosted economic growth in some countries of the Horn region, its great mass of people still lack access to even the most basic human necessities. More should be done. In this regard, Japan’s and France’s geopolitical approaches can be exemplary as the two have allocated resources that support the development and human security in the Horn of African states. India has, ironically, been an outlier in the region. The deployment of Indian soldiers to serve the U.N. Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) have little political influence on the regional security architecture. The U.N.’s mission of sustainable peace is supported through Grant Assistance for Grassroot Human Security Projects (GGP), which focuses on human security issues. Therefore, ideal geopolitical involvement in the Horn should combine essential human security and development elements.

The network of connections that influence the Horn’s political landscape results from competition between Middle Eastern governments and interactions between significant foreign powers. Different local, regional, and international incentives exist for every foreign participant to be present in the Horn. The geopolitical ups and downs have not affected India’s relationship with the Horn; its indulgence has mainly been restricted to anti-piracy patrols at sea and peacekeeping missions on land. However, the expectation of global leadership has increased with India’s nomination to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) for the years 2021 and 2022. The best approach to getting the world’s respect is to show that you have global importance. India would thus need to exert tremendous effort in the Indian Ocean Region’s littorals by focusing on human security and sustainable development. In this regard, India might realign its Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) philosophy using the conceptual framework provided by the United Nations’ objective for sustainable peace.

In terms of development, the World Bank has designated Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea as Fragile and Conflict-Affected States (FCS) for the fiscal year 2021. The obstacles to advancement are just as common in Africa as in the Horn. Multidimensional inequalities and unfair wealth distribution are manifested in the region’s vulnerability to widespread poverty. Additionally, horizontal disparities based on racial, gender, linguistic, religious, and cultural identities feed societal unrest. Other concerning megatrends that influence the economic, political, and social environment are the COVID-19 pandemic, rapid population rise, migration, and urbanization. Forecasts indicate that the temperature will increase and that coastal regions will experience more frequent flooding. Risks associated with disasters would result in the loss of infrastructure, crops, and livelihoods, which might cause civil instability and mass migration. Furthermore, by 2050, the majority would probably be forced to live in urban slums due to the high population increase. Most people in the Horn experience structural and physical violence in their daily lives because there is no political leviathan.

Ethiopia’s extraordinary economic development over the past two decades has brought about stability and regional collaboration, encouraging peace and security. The Horn of Africa is blessed with abundant natural resources, a sizable agricultural area, and the Nile, one of the world’s longest rivers. Fossil fuels, mineral resources, and fishing are significant economic contributors. Any attempt to sustainably engage the Horn would require a regional strategy with Ethiopia at its center. China’s Djibouti-Ethiopia model is instructive in this regard.

Human security, broadly described as being free from both fear and hunger, is closely tied to many facets of economic progress. The Horn of Africa yearns for a lasting peace that places people at the heart of prosperity and security, in contrast to its people being exploited by colonial powers who have continued interfering in the region that has resulted in decades of strife. Regional integration seems to be the most practical plan for quick expansion given the current Horn conditions. The best course of action is to invest in the economic corridors that connect Ethiopia with its maritime neighbors. However, this development ought to result in peace and security for people. By definition, SAGAR, the foreign policy concept of India, coincidentally combines security and development. But is it a workable plan for fostering long-term peace in the Horn of Africa?

Growing evidence suggests that the geopolitical rivalry and direct and indirect international interventions by extra-regional or outside actors have been ineffective in resolving complex and protracted conflicts in the global south, but instead enabled patrimonial politics and authoritarianism. Inequality, lack of opportunities, discrimination, and exclusion have also fueled complaints and perceptions of injustice. In most African governments, poor governance leads to transnational crimes such as terrorism, violent extremism, human trafficking, forced migration, and illicit money flows. To take the author’s recommendations seriously would require that geopolitical interests and rivalry should prioritize societal development and security over militarism and partisan politics in the target region. Extra-regional actors must follow human-centered geopolitical approaches to bring about sustainable peace in the Horn of Africa. If geopolitical players follow the author’s presumptions, the Horn of Africa’s politics and strategic position may favorably influence peace, development, democracy, property, and human security. However, if these presumptions are not taken into account and geopolitics in the Horn of Africa continue to be characterized by militarization and mutually-exploitive politics between local actors and their international partners, the region will continue to be plagued by state collapse, civil war, human trafficking, and terrorism.

The Horn of Africa has been increasingly important over the past 20 years, and the area has begun to serve as the IOR’s strategic pivot. India must thus shift its attention to this important geographic location. Because of the ongoing violence in the area, the smaller nations are more susceptible to political and social upheavals. In this context, Ethiopia’s demographic dividend, political influence, and geographic center give optimism for regional prosperity and integration. As a result, the Horn of Africa’s regional integration, with Ethiopia at its center, is a workable way to promote economic development and stability.

According to the logic presented in this article, India’s SAGAR foreign policy philosophy, which conflates security with development, is consistent with the U.N.’s goal of sustainable peace. SAGAR, however, is unduly concerned with maritime governance in its current form. India’s approach to the region should consider good governance, growth, and human security.

India has to contribute to global concerns, not just in word only, but actually build its worldwide presence to impact global consciousness visibly. While moving forward would require risk-taking, India should avoid misrepresenting caution and hesitation as wise decisions. Undoubtedly, the Horn of Africa poses a variety of challenges. Still, it also presents India with tremendous potential to position itself as an advocate for international stability and security, particularly in light of its participation in the U.N. Security Council in 2021–2022. India must thus redesign SAGAR Version 2.0 for the Horn of Africa by coordinating its foreign policy with the U.N.’s objectives for sustainable peace.

By: Jemal Muhamed, CIGA Senior Research Associate