Author: G. John Ikenberry

Affiliation: Princeton University

Organization/Publisher: International Affairs

Date/Place: December 08, 2024/USA

Type of Literature: Research Paper

Word Count: 10129

Link: https://bit.ly/3Sn8tPp

Keywords: Global Order, Global South, Liberal Hegemonic Order, the West, the East

Brief:

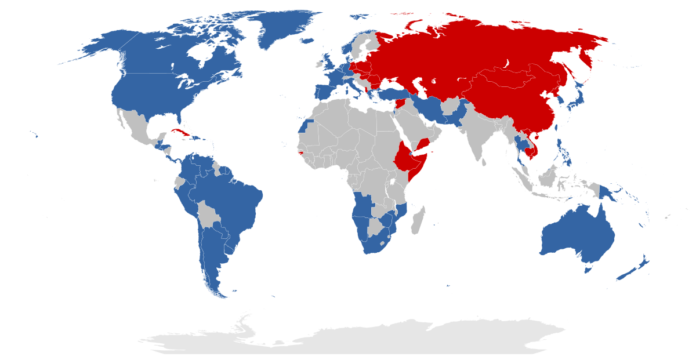

This article frames the current global state of affairs, with the decline of the US-led unipolar world, and the rise of other poles, as a return to the system of Cold War-like geopolitical divisions and ideological groupings. In this regard, Ikenberry theorizes that the contemporary international order is divided into three poles or ‘worlds,’ namely the Global West led by the US, the Global East led by Russia and China, and the Global South led by countries such as Brazil and India (referred to hereafter as West, East, and South). These new worlds, in Ikenberry’s view, are defined by their perception of the Ukrainian war and how it fits into their narrative and pathway to modernity, as well as the quest of each to reshape international norms and inter-state behavior. However, a distinction is made from the older camps that shaped the Cold War. Today’s blocs are, in Ikenberry’s words, “informal, constructed, and evolving global factions, rather than fixed or formal political entities” with those coalitions being “situation-specific, activated by the conflicts and controversies of the moment.” Meanwhile, even though he acknowledges that China has attained the status of a ‘pole’ in terms of the traditional measurements of power capabilities, including economy, military, technology, and demographics, Ikenberry nonetheless does not classify the global system as bipolar, as he believes that such a dichotomy would dismiss the key role played by the South.

Having established the core aspect of this new global order, Ikenberry further outlines the characteristics of the three-world system: 1. It is durable and irreducible, since all three groupings have lasting political visions. 2. In the three world system, the East and West will compete for the support of the South. 3. The common rules shaping this world are a mix of principles established in Westphalia (territorial sovereignty and non-intervention) and principles established in the UN charter (sovereign equality, self-determination, sustainable development and social justice, and human rights) and; 4. While it does not have complete hegemony, the West is still the most powerful, thanks to its supremacy in the military and technology domains, as well as democracy. Furthermore, as it relates to points 3 and 4, Ikenberry argues that the South’s critique of the West “is not that it offers the wrong pathway to modernity, but that it has neither lived up to its principles nor shared sufficiently the material fruits of liberal modernity.”

As mentioned earlier, Ikenberry’s hypothesis rests on two key presuppositions, namely the Ukraine war as being a milestone development, and each of those worlds attempting to reshape the global order based on a certain narrative. For the West, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a threat at a security and principle level, including the violation of what he dubs as the holy trinity of Western principles: prohibiting the use of force to annex a neighbor’s internationally recognized territory; no killing of innocent civilians as a tool of war; and prohibiting threats to use nuclear weapons. All of these have been established in the UN Charter and the post-Cold War security agreements in Europe. As such, the West wants Putin to fail and pay a heavy price. On the other hand, Russia wants to fight back the encroachment of the Western order, which is a claim they have marketed to the capitals of the South. While Beijing, who has benefited from the West-endorsed open market, does not completely support taking down this order, it has shown sympathy with Russia’s narrative of a new post-West, post-American international order. Moreover, China’s stakes in this war are linked to its aspiration for global leadership, the Taiwan issue, and its desire to expand its influence in East Asia and the non-Western world. The South, in the meantime, remains on the sidelines, as it faces a complex calculus in its position of neutrality and non-alignment, despite the symbolic condemnation of Russia’s action. The South wants to support principles such as non-intervention and non-coercion, yet it does not want to support American hegemony. To Ikenberry, Brazil’s position on the issue is emblematic of this calculus. Nonetheless, the article concedes that these developments give the South more room to maneuver.

At the core of this West-East conflict lies different “logics” of world order, that is of a liberal order versus an illiberal order, with the former defined by security pacts and partnerships among liberal democracies, and the latter resting on the more traditionally realist view of regional blocs and spheres of influence, as well as autocracy. Ikenberry then underlines the profundity of the impact of China’s rise, which has altered the global order on three fundamental levels: 1. In a traditional sense; 2. Being the first non-western Superpower and; 3. Pitting a conflict between the liberal hegemonic order and an illiberal hegemonic order. This then is a struggle of power, ideas and geography. He also points out that it is difficult to separate between the West as a liberal order and as a US-centric hegemonic order, which further complicates the matter.

In the three worlds order, the South sits at the periphery. For instance, the South is the only one of the three blocs with no permanent seat on the UN Security Council. The South is also defined by its aspiration for development, voice and status. Nonetheless, the South has capacities that manifest in two key assets in Ikenberry’s views. First, the South is a swing vote/support for either the East or the West. Both camps need the South, because neither can establish an international order on their own because they lack the “critical mass”. Therefore, each camp tries to offer public goods to the South, since both camps are aware of this fact. A manifestation of this is Washington and Beijing trying to appease the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASAN). Second, the South can confer legitimacy to the narrative of either camp, or give it “narrative power” as Beijing puts it. This also underscores the fact that the South itself has no “enlightened views about the proper organization of world order.”

Broadly, Washington provides security, while Beijing makes for an attractive trading partner. China is selling its development model to the South, with many countries looking to emulate that model. Furthermore, the South might be tempted to join forces with China to fight global US hegemony. On the other hand, an alliance with the West is an alliance with the most formal and coherent bloc. Additionally, a number of countries of the South are more attracted to the idea of building democracy, rule of law, and institutions. This again highlights the complexity of the South’s so-far aloof position: security assurance from the West, or trade with the East. Nonetheless, this also highlights the importance and potential the South holds going into the future. For one, the South represents a large part of the world’s population. Furthermore, there is also the rise of a number of key states that are situated to become important geographic and economic players, such as India and Indonesia in Asia, Brazil in Latin America, and Türkiye in Europe and the Near East.

As a manifestation of this three worlds system, both the US and China will seek to build better relations with key states outside their orbit, evidenced for instance by both Beijing and Washington trying to improve relations with Saudi Arabia, while at the same time trying to prevent countries from joining the other camp. This also marks how ideology is not an important factor like it was in the Cold War. Furthermore, each of the two blocs will try to offer better public goods, which Ikenberry views as for the betterment of the world. Both will also try to appear less disruptive and not responsible for world crises, since global hegemony is more durable when it appears as legitimate, which involves normative appeal. Another outcome of this three worlds order is the changing of the rules underlying the global order.

Finally, the article argues that neither the East nor the West will be able to absorb or win the South completely. Rather, this three-world system will sustain itself for the foreseeable future. However, the article reiterates that the West sill have the advantage for a number of reasons, including its experience in establishing the world order, which, Ikenberry claims, have ultimately made the world a better place. “There is widespread dissatisfaction today with the existing international order, a view held inside the West as well as in the global East and global South. But the liberal states in the West are in the best position to offer leadership in the reform of this order. Secondly, neither the East nor the South have new ideas on how to replace the existing world order. Lastly, the liberal order has a fundamental key-solving aspect that gave it its strong durability, with the Western states still having a role to play.

By: Hamza Ghadban, CIGA Research Intern